- 1. Traditional Giving Losing Relevance in Today’s Environment

- 2. LEAN Philanthropy Framework

- 3. Experiments in the Field

- 4. Learning from the Experiments

- 5. Philanthropy Education’s Larger Mission

- 6. Awaken the Sleeping Lion for a Better Shared Future

- ChangeLog

1. Traditional Giving Losing Relevance in Today’s Environment

1.1 Historical Reflection Reveals Disconnection from “Philanthropy”

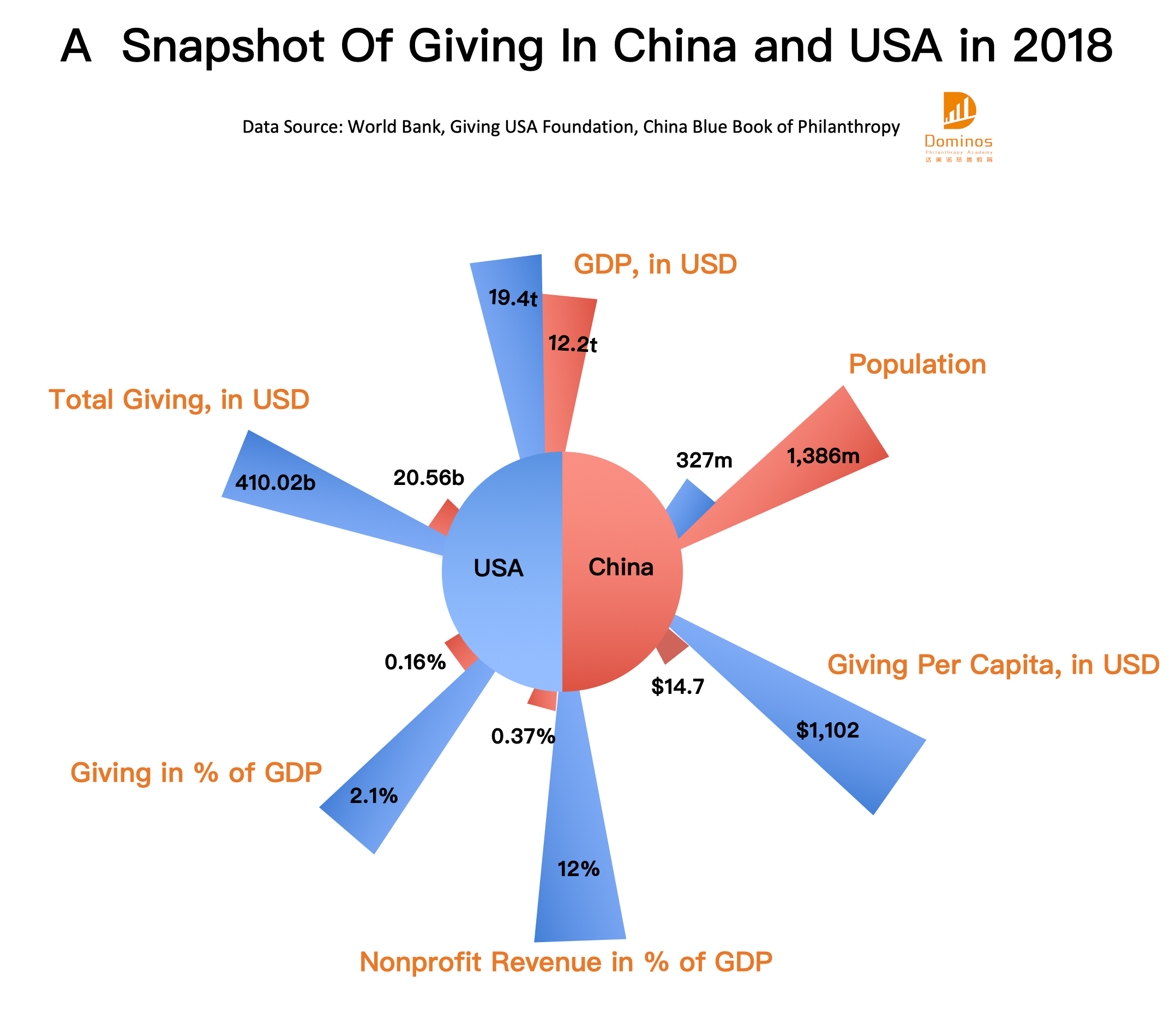

In the World Giving Index 2018 report, China was ranked 142 out of 144 countries. China has placed at the bottom since the Charities Aid Foundation published its first annual report in 2010.

How can this be? Giving is not a new concept in China. One of the core Confucius teachings is benevolence (仁), encouraging people to be kind and to help one another. The Chinese economy has developed fast, and people’s disposable income has grown 59.2 times since China was founded in 1949. Is economic development making Chinese people less generous?

A lot of explanations have been offered to solve this puzzle, such as inadequate infrastructure for giving and lack of a transparent social sector. These reasons make sense. At the same time, diving into China’s history of giving has led us to another observation - the traditional approach of giving is losing relevance in today’s China.

Traditional Chinese giving has three main characteristics. Firstly, it was largely kinship-based, or relational, giving. This meant giving to members in the extended family or people from the same geographic area. Secondly, giving was often charity-oriented, mostly to meet immediate and basic human needs. Lastly, giving decisions were usually made top down by elders and leaders – ordinary people didn’t have much say in giving decision-making.

This kind of giving worked well for thousands of years, when agriculture was the dominant economy in China. During that period of China, generations after generations lived in the same village. Food and shelter were major needs. In an authoritative society, having elders making decisions wouldn’t raise questions in people’s minds.

However, the fast economic growth of the last 30 years and political shifts since China’s founding in 1949 have drastically shattered the environment where traditional giving lived.

The first force is urbanization and industrialization. People have moved out of the villages into cities. They live in neighborhoods with little interactions with one another. Meanwhile, the one-child policy has significantly reduced the size of the “extended” family. The social fabric in which traditional giving thrived has dissolved.

Another major influence comes from government and the changed social structure. After People’s Republic was founded in 1949, the government assumed the responsibility of providing public good, and philanthropy was discontinued. China’s first NGO didn’t come into existence until 1995. It’s not until the late 2000s that nonprofit organizations started to flourish. People were mostly removed from community engagement and addressing social issues. Several generations have grown up with little giving or volunteering experience, and are now the mainstream leaders and educators in our society.

Despite the economic growth, the giving tradition in China didn’t get equivalent developmental opportunities. Today’s pervasive attitudes and behaviors toward giving often reflect the traditional mindset of giving. For example, to many Chinese philanthropy is mainly giving money or materials, people rarely give to strangers, and donations by individuals stay low unless in times of disaster.

The charity-oriented lens carried from the agricultural economy also limited people’s vision regarding philanthropy’s potential larger role in society, such as individual development, building relationships, increasing social capital and creating social change. Despite the rapid growth in the number of foundations from 557 in 2000 to 7027 in 2018, more than 99% of them are operating foundations focusing on projects. Only a very small number of foundations take the grantmaking approach to drive social change.

Due to lacking adequate knowledge of and direct experience with nonprofit organizations, it’s easy for people to be skeptical. A lot of netizens questioned the agenda of Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s trip to China in 2010, and skepticism toward the sector hasn’t dissipated after a Red Cross Society scandal, which later proved to be false.

All these factors may help explain the low participation in philanthropy among the Chinese, even though many have means to give.

In short, the transition in the social, economic and political life of the Chinese disrupted traditional giving, but new giving norms have not yet been established. People are disconnected from philanthropy.

1.2 In-depth Interviews Lead to New Insights

To test our observations, we conducted in-depth interviews in Shanghai with 20 middle and upper middle class professionals, with a wide range of ages between 30s and 60s. Their backgrounds are very diverse in terms of industry, position, and life stage.

These interviews to a large extent confirmed the disconnection we had learned from our historical reflections. While not surprising, it was still striking to hear most of them describe giving as something external, distant and intended for the future.

However, something promising emerged during the interviews. Many people started asking questions about purpose and meaning in life, and cared very much about personal growth. Many had started exploring these topics through religion, pursuing hobbies, or taking courses.

The interviewees also expressed a desire to connect with others, and to make a positive impact.

This is truly inspiring. China has always been an authoritative society. Many of us were taught to follow paths set by others – by parents, teachers, supervisors, or society norm. This may be the first time in this ancient country that ordinary people are starting to ask such questions on their own.

Despite their efforts to pursue a meaningful life, due to the disconnections we discussed earlier, not many of those we interviewed have realized that taking philanthropic action can help them on a path to their destination.

2. LEAN Philanthropy Framework

Thus the path emerges. If we can help people make meaningful connections with philanthropy, and have positive giving and serving experiences, maybe we can unleash the potential of individual giving in today’s China.

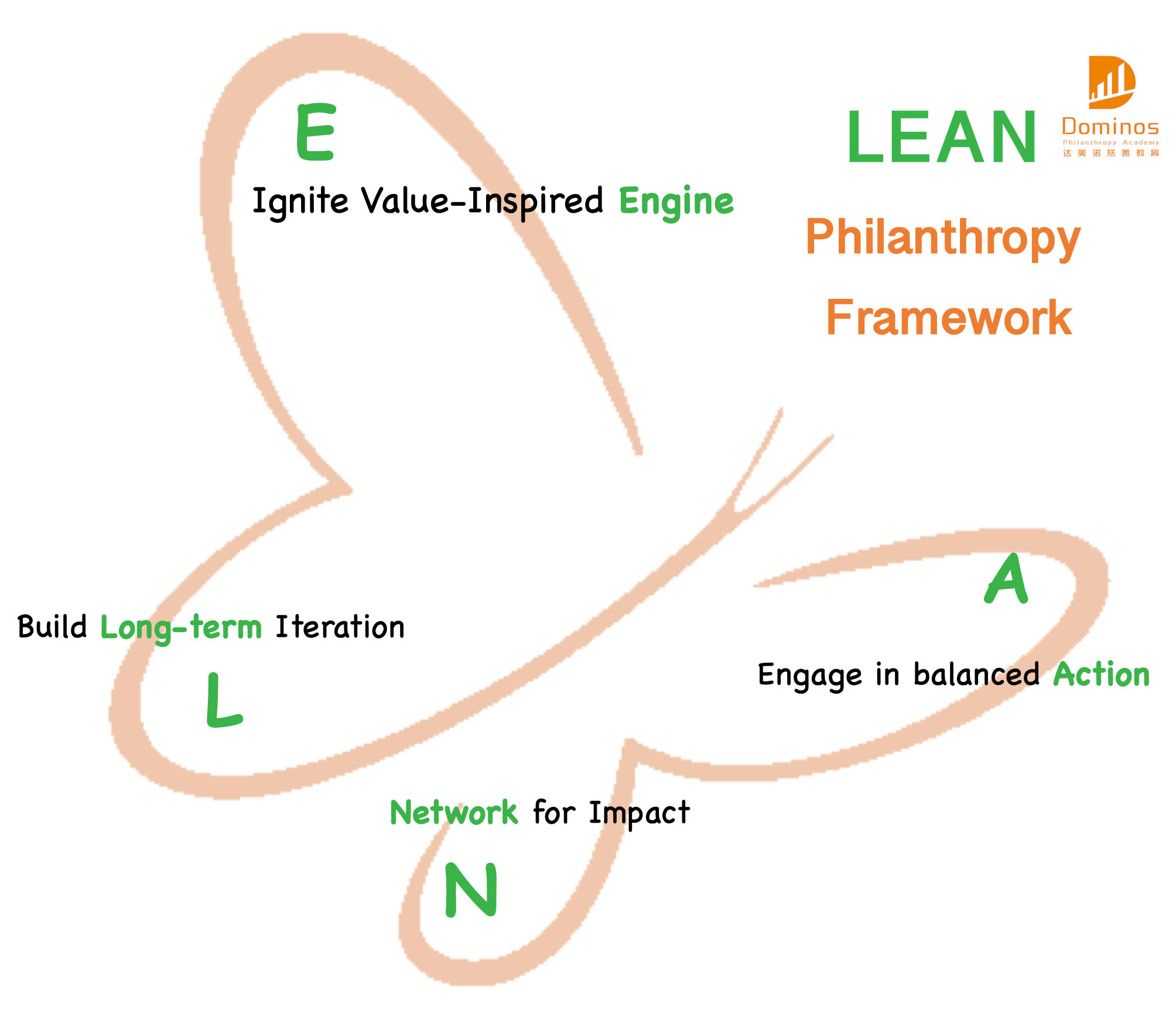

The challenge at this early stage is to develop easy to understand concepts and easy to use tools for people. With support from Narada Foundation, we designed the LEAN Philanthropy framework.

This framework identifies 4 key factors that could inspire individuals to act on their values and passions, and sustain their philanthropic actions. The framework has an acronym LEAN, visualized in the shape of a butterfly. Just as you might be wondering, the framework was indeed inspired by theories and practices on lean manufacturing and lean startup.

To start with, L is for Long-term learning and iteration. We want to help people understand that giving and learning is a process, not an event or activity. If we constantly examine where we are in this process and continuously improve, we’ll get better at giving.

E is for Engine. Each person has a unique philanthropic spark, which we define as the sweet spot of values, talents and interests. That’s the engine to ignite.

A is for Action. More specifically, we encourage Minimal Viable Action. When we engage in giving, it should be satisfying enough to provide momentum to continue, but not too much to the extent that it would wear us down.

N is for Network and connection. We need to connect with beneficiaries, fellow contributors, and people who are not yet giving.

The 4 factors form a reinforcing feedback loop. Ideally people will start with E. Practically, they can enter the loop at any place. As long as they get these 4 factors, it will lead to meaningful and satisfying giving. If people keep going, this loop can turn into an unstoppable flywheel. People will give more, satisfy more, learn more, and their giving will become more impactful.

We have also developed a set of self-assessment instruments called the LEAN Index. From those who have tested the instrument, the index can offer them a tangible idea of where they are now in their giving, and how they can improve in their giving.

3. Experiments in the Field

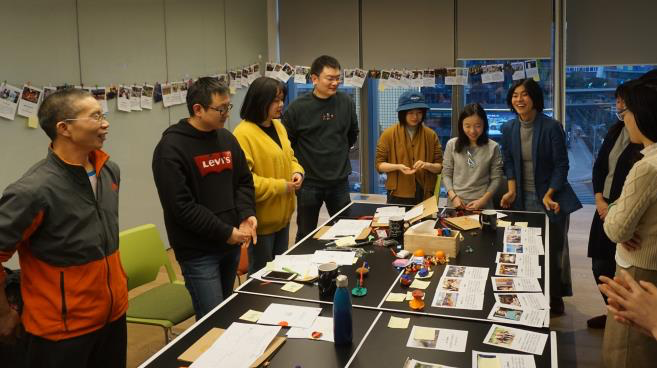

It took a while to figure out how to best help people understand the concept and willingly use the tools. Through several tests, we realized that interactive educational programs would work best in today’s environment.

We designed and delivered a series of experiments using the LEAN philanthropy approach and tools. For each experiment, we would like to seek: 1) Does the program help people better connected with philanthropy? 2) Does the program inspire action? 3) Does the program help personal learning?

3.1 Experiment 1: Spark Workshop

In February 2019, we had a 2-session workshop to help participants figure out their philanthropic spark (that is, their Engine). Each session took half a day. 16 participants from diverse backgrounds got together. Among them were college students, young professionals and senior executives. Some had never volunteered, while others were veteran volunteers.

We took them on an interactive and experiential journey to explore their values and purpose, their relationship with others (including strangers), and the issues they care about.

For each of them, it was the first time that they had connected their personal values and experiences with social issues. It was even so for the person working in the social sector.

Many participants described the experience as “eye-opening” and “mind-blowing”. One young professional shared her story of verbal bullying in her family when growing up. As a TEDx organizer, she planned to use the TEDx platform to raise awareness of these issues and look for opportunities to support education on healthy family dynamics.

An executive at a private bank had participated in almost every volunteer program to teach in a remote village through the bank’s Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives. Only at the workshop did she realize that her spark was mental health. She felt liberated when she learned that she can actually combine her passion with social issues. That was something she had never known before. A few months after the workshop, I encountered her at an experiential grantmaking event where she was to learn about the NPO’s work helping kids with mental health issues. It was great to see her move forward to bring her spark to action.

3.2 Experiment 2: Middle School Philanthropy Course

The more we understand the historical gap in giving, the more we are concerned for today’s youth, who want to do good but can’t get enough support from parents, teachers or the community.

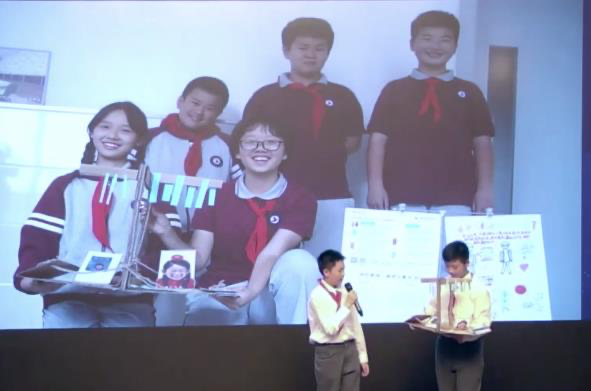

Between September 2018 and June 2019, we conducted a two-semester experiment at a public school in Shanghai by offering the nation’s first philanthropy course to a class of 6th graders. We wanted to see whether and how we could make philanthropy relevant to these young minds, even though they had little or no experience in serving or giving.

We spent the first semester exploring concepts around philanthropy, such as motivations for giving, the 4Ts (Time, Talent, Treasure and Ties), community heroes, etc. We also explored their own interests and talents.

During the second semester, we took the students on a Project-Based-Learning journey, partnering with Shanghai United Foundation (SUF). 40 students were divided into 5 teams. Each team picked a project supported by SUF, researched the social issues, and created exhibits to raise awareness of these social issues.

Their work was truly amazing. One team used steep Lego staircases to illustrate the insurmountable obstacles for a job seeker with a disability. Another team used paper strips to symbolize sunshine and rain, representing love and care from parents. The team gave “left-behind” children from rural China very thin strips of paper, because, on average, they only saw their parents twice a year. By comparison, kids in the cities got wide strips of paper, as they were showered in parents’ love every day.

At the end of the semester, they presented their work to the whole school. They wowed the audience of teachers and peers.

In the summer, the class voluntarily organized service projects to help seniors and kids in a local hospital. Considering such student-organized volunteering is not common in Shanghai’s public schools, I am very happy to see they have taken the initiatives to do something.

4. Learning from the Experiments

Besides these two experiments, we also experimented with the LEAN framework with elementary school students and families through workshops and service learning programs.

The feedback was very positive. People who have gone through our programs want to do more. Some of them have already started to act. It’s safe to say the idea of helping people make meaningful connections with philanthropy has proven to work.

We have learned much along this journey, while several lessons stand out.

4.1 Philanthropy education can be a practical and effective approach.

Compared with counterparts in many western countries, everyday Chinese don’t have as many opportunities to engage in philanthropy, as our country’s nonprofit sector is still nascent. Education can be a practical way to equip people with knowledge and tools so that they can take initiative to create their own opportunities.

The LEAN philanthropy framework can serve as an effective entry point to help people get their heart and mind in the right place when they start. Once they can identify with needs and social issues, they can take their abundant resources and go in whichever direction they want, whether it’s participating in direct service, engaging in impact investing, or changing business practices.

To make such educational programs effective, from our experience, interactive and experiential learning is very important. Traditional training styles and approaches may risk putting people off.

4.2 Ignited sparks may channel support to underfunded issues.

We stumbled upon a funding source that could be significant.

Statistics show current individual giving addresses the same issues where the government focuses, mostly human service and social welfare, such as poverty.

During our work with individuals, it has amazed us how diverse people’s philanthropic sparks are, many of which went far beyond governmental funding focuses, such as parenting support for migrant workers and arts for underprivileged kids.

If people can ignite their personal sparks, we should be able to expect individuals to step up for issues neglected or under-funded by government, which could help build a foundation for a stronger civil society.

4.3 Two obstacles may hinder individual giving.

Going forward, we can see two obstacles stand in the way of stimulating individual giving.

The first obstacle is inadequate infrastructure to support people researching nonprofit organizations and social issues in a way they can understand or that allows people to find volunteer opportunities. Several people from the Spark Workshop have reported these types of challenges.

The other obstacle is nonprofit organizations’ limited capacity and capability to create mutually beneficial relationships with their contributors. It’s common to hear complaints from volunteers (especially college students) about their negative experiences.

5. Philanthropy Education’s Larger Mission

5.1 Revive China’s Giving Culture

Although the space of philanthropy education in China is new, some plausible efforts are budding.

With support from SongQingLing Foundation and China Foundation Center, Beijing Normal University ZhuHai Campus started the country’s first program to train foundation professionals in 2012. This program has graduated 221 students, 60% of whom are either playing important roles in foundations, or pursuing higher education related to the social sector.

China Global Philanthropy Institute, funded by Bill Gates, Ray Dalio, He QiaoNv, Niu GenSheng and Ye QingJun, offers an Executive Management of Philanthropy program to High Net Worth Individuals.

DunHe foundation has recently started an initiative to support universities with nonprofit and philanthropy major programs. They plan to expand their efforts in philanthropy education.

Most current philanthropy education programs aim to strengthen organizational capacity in the social sector, and focus on the technical competence. It’s very important, especially when the nonprofit sector in China is at such a nascent stage.

At the same time, putting together what we have learned in the last year and a half, I can’t stop wondering this question: Can philanthropy education have a larger mission to revive China’s giving culture, which can reflect today’s societal and individual needs, so that giving and serving becomes part of every Chinese person’s life?

The new giving culture can eventually lead to more intentional and impactful giving, higher engagement in the community and society, richer social capital and eventually a stronger civil society.

5.2 Seek Areas of High Leverage

Reviving a country’s giving culture seems daunting, especially for a country with thousands of years of continuous history, whose legacy of giving has become the burden.

If we could start with those who are already looking for change and whose change can lead to high impact, the mission could be less challenging.

Through learning from our own journey, I’d like to propose focusing on two segments of society and one practice that may lead to significant leverage.

The first segment is college students. Many of these young people are already seeking purpose and opportunity for positive impact. Meanwhile, within a few years, they will be professionals. In a few more years, they may be parents. If they could get more education on and exposure to philanthropy, we have reason to expect a much higher chance for them to be more informed and engaged givers after college, whether they end up working in the nonprofit sector or not.

The second segment is youth and family. Only a very small percentage of families in China have had experiences giving as a family. Speaking of philanthropy, most parents are as inexperienced as their kids. Many parents have expressed to us that they want to learn more about philanthropy and want to do good with their kids. There is a great opportunity to engage both generations on a learning journey of giving.

The one practice we see as having great potential leverage for the growth of Chinese philanthropy is grantmaking. Grantmaking is a new concept in China. Among over 7500 foundations in China, probably less than 30 foundations are grantmaking foundations. The rest are operating foundations.

We might need to take baby steps to help people understand grantmaking through approaches like giving circles and student philanthropy.

Once more individuals in China adopt the grantmaking practice, the impact can be multiplied. Givers can build better understanding of social issues through direct experiences with nonprofit organizations. This would be an important step, given that service opportunities are not accessible for everyone yet. At the same time, NPOs would have access to financial resources that are hard to obtain, as there are just a handful of grantmaking organizations in China.

Given time, maybe we can even expect more foundations to adopt grantmaking.

6. Awaken the Sleeping Lion for a Better Shared Future

China was once called a sleeping lion. Although China has woken up economically, the unleashed giving capacity of individuals and unrealized philanthropic impact make today’s China like a sleeping lion.

In recent years, there are signs that this lion is about to awake.

Government is encouraging citizens to give, serve and build community. Technology has enabled more and more Chinese to give with a click. Online giving contributed 2% of the total giving in 2017, and is increasingly popular among young people.

Consistent with millennials in other parts of the world, millennials in China have also demonstrated keen interest in societal issues and impact. College and high school students are initiating a lot of voluntary projects. Young professionals in cities like Beijing and Shanghai are starting grassroots efforts to make their communities a better place.

In this global economy and hyper-connected world, no country exists in a silo. We all share the future. Philanthropy is about connection and action. If we can awake Chinese, who represent 1/5th of the population on this planet, to take action on issues they care about, we can expect the whole world can become a better place.

For our shared future, we can’t afford to see a class of 6th graders studying in a school where the only giving event is donating clothes and growing up in a family where no parent has ever volunteered. And we can’t afford for millions of college students to head to rural areas every summer because they think teaching in a village is the only charitable thing they can do.

To achieve change, it’s important for us to help the aspiring new generation to, first, identify with philanthropy, and then connect them with philanthropy’s larger vision and role in society, supporting them along their journey.

Like many other trends in China in the last 40 years, we have a time window when we can have an impact. The new generation is shaping their views and visions on purpose, philanthropy, and their place in the society. How we act within this formative time may determine where philanthropy in China will lead for generations to come.

The clock is ticking.

ChangeLog

ChangeLog

- 200207 Minor Edits

- 191003 Final draft

- 190922 Sending out for Critiques

- 190915 first draft done

- 190914 Add Philanthropy’s larger mission

- 190908 Restructure

- 190831 Create